The False Dichotomies of Comics

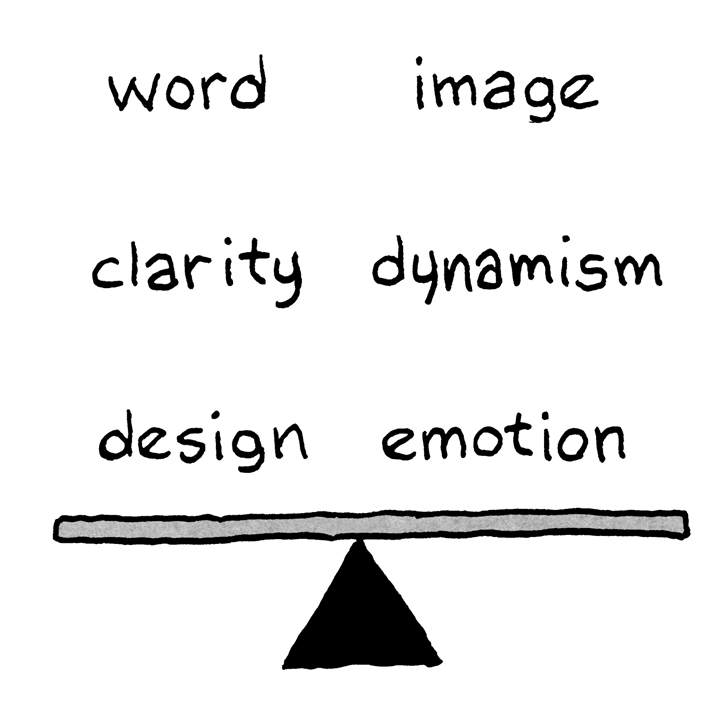

We have all encountered comics that have sacrificed a concept on one side of the balance beam for one on the other. For instance, many comics have an engaging style of drawing but seem to take no care in the quality of their writing. Or they are so interested in visual dynamism that they sacrifice reading clarity. Or they focus so much on design that they become emotionally stiff and cold. These concepts can be useful on the analytical side of things, when we are trying to describe a comic that we are reading. But the idea that these must be dichotomies is, at best, limiting to an artist and, at worst, flat out wrong. Yes, the elements in these pairs of terms are different, but they do not have to be in opposition. Assuming that they do can be an unnecessary obstacle.

In a general sense, art is often about breaking boundaries and defying expectations. Art does things and makes us see things in new ways. These dichotomies give the impression that an artist has to choose on which side of the fulcrum they lie. Again, that is a false and misleading choice. Artists who make supposed dichotomies nonexistent are usually labelled geniuses.

Word – Image

Looking at the first pair, we all know that words and images are different and a lot has been discussed about this. In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud claims that pictures are “received” and text is “perceived” (49). He even draws an artist and writer separated by the chasm of that dichotomy (48). McCloud attempts to solve the dichotomy by bringing in a third element, the picture plane (51). Basically, abstraction is a way to bring the two opposing sides of word and image together. This is an intriguing idea and gets us away from the either/or fallacy, but the result is a three dimensional scatter plot that still implies an artist exists somewhere on a measurable spectrum.

Fundamentally, I see this dichotomy between word and image to be fueled by the history of comics creation, specifically the bullpen approach in which writers and artists are different people. For many comics artists, myself included, a concept for a comic comes in words and images. The two are part of a package which includes larger elements of plot, mood, and design. I am not saying that words and images are the same, but focusing on them as opposing elements creates an unnecessary conflict. In creation, the goal is bigger. It is the concept itself.

Also, in a comic, words and images are both ink on paper. And so there are many creative ways to integrate them. I think manga has a strong history of this (to generalize). But we can look outside comics, to concrete poetry, for instance.

image from Wikipedia

Clarity – Dynamism

The clarity/dynamism dichotomy is one that should be obviously false. You can look to the long history of art for examples of dynamic images that read easily. In comics itself, artists like Alex Toth, Jose Muñoz, and Taiyō Matsumoto exemplify the fact that readability and visual excitement are not mutually exclusive, even in plain black and white. I think a lot of “dynamic” comics are unreadable because the artists have a limited view of what dynamic means. They confuse dynamism with density. Lots of hatch lines, minute details, and crazy angles do not equal powerful art. On the other end of the spectrum, readability becomes a golden calf that some artists worship. Personally, I prefer readability, but it is not the enemy of dynamism. I think this is why many contemporary artists have turned to newspaper comics from the early 20th century for inspiration. The best of these comics marry dynamic drawing and design with clear storytelling that was intended to be read by a general audience. Again, I think the solution for the artist is to broaden their influences.

Design – Emotion

In Making Comics, McCloud creates four different camps of artists and separates those who care about design, the “formalists,” from those who care about emotion, the “animists” (232). His focus is on what the driving interest of the artist is. This makes sense and we can think of examples that fit his categories, and he offers some of his own. Yet, again, the problem with this is that it oversimplifies the artistic drive as well as human nature. People seldom have one clear desire. To be fair, McCloud acknowledges this and says some artists are members of two camps, but asserts that usually they are never both formalists and animists. The two are mutually exclusive. I remember being upset when I first read this. I felt that I was interested in the formal elements of comics precisely because I wanted to uncover more ways to express emotion. Around the same time I received a review in which the reviewer labelled me a formalist and seemed not to see the emotions I was going for in my work. Now of course, the failure may have been on my part. Yet I also think this shows that this belief that emotion and design are two opposing forces is prevalent.

To which I ask: has no-one heard of graphic design? Has no-one read Chris Ware?

As always, this is a matter of taste. I have read people who feel that Chris Ware’s layouts are too stiff and make his comics seem cold and emotionless. Personally, I can’t think of many artists with more emotion pouring through their work than Chris Ware. I also think some readers don’t see how the emotions in the narrative of a comic can play against a static layout. A repetitive grid can provide a contrast for the other elements in the work to play against. But mostly, as I said, I firmly believe that explorations in formal design are also explorations into finding new ways for the art form to express the human condition. They are not opposites. In fact, the one is the key to the other.

Overall, my point is that we often find ourselves defining things too narrowly and this hurts our ability to create and limits our scope of what is possible. As I get older, I am uncovering more and more little “rules” that I have made for myself that get in my way. I am not opposed to working within limitations or believing in a personal manifesto, I just want to understand the ways that I get in my own way unnecessarily. This was an attempt to do that.

As always, the solution lies in personal introspection and a diverse source of inspiration.

I forgot that Jesse Hamm wrote about the dichotomy between craft and vision back in 2012. He uses Moebius as an example of someone who deconstructs the dichotomy.

https://sirspamdalot.livejournal.com/87692.html

Thanks, Jesse.