The Street of Crocodiles and Other Stories by Bruno Schulz

I was lead to Bruno Schulz by the Brothers Quay. Their version of Street of Crocodiles is one of my favorites of their films. Now having read the source material, I can see a connection in the dream reality and empty city streets of both. But the Brothers Quay have a cruelty in their work that Schulz’s work lacks. In its place, Schulz has a Romanticism that lies in contrast with the Modernist settings and conflicts of his writing.

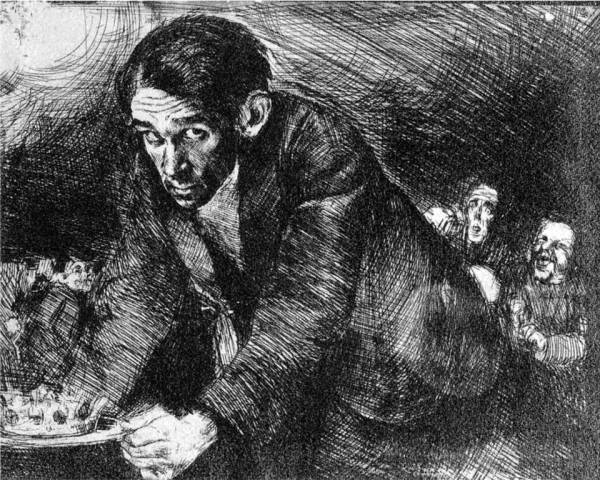

Schulz was born in 1892 in a small town in Poland, Drohobycz, where he basically stayed his entire life. He was a writer as well as an artist. In fact, he taught art to high school students as a way to support himself. Personally, these details draw me to him since they are a fun house mirror of my own biography and I must admit I hoped that Schulz’s drawing and writing may have merged at some point. Yet if there is a Schulz comic, it is locked in the lighthouse in Hicksville. As far as I can tell, the only melding of his writing and drawing came in the form of illustrations for his stories.

From the accounts, Schulz was a modest man who focused on the development of his art more than the grooming of his image. Yet he did begin to acquire a small amount of fame in his early forties. Unfortunately, and tragically, this fame coincided with the start of the Second World War. The Nazis came to power. And Schulz was a Jew. His artistic abilities got him noticed and a gestapo officer ordered Schulz to paint murals on the walls of his child’s playroom. Yet another officer had a grudge against Schulz’s officer and so used Schulz as a means of exacting his revenge. Schulz was shot dead in the street.

Apparently, Schulz had been working on his masterpiece, entitled The Messiah. The manuscript of this work didn’t survive the war. The murals did however, as did his two collections of stories, Cinnamon Shops (known in the U.S. as the Street of Crocodiles) and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass. These are collected in the book I read.

One cannot read these stories as one reads most stories. Schulz’s work has less in common with the plotting of traditional narrative and is closer to the lush metaphors of Romantic poetry or the thick movements of oil on canvas. His stories are dream-like and surreal. He is often compared to Kafka, but where Kafka stays focused on one image and takes it to its conclusion, like in The Metamorphosis, Schulz offers us image after image. His writing is like a decaying bouquet, heavy with perfume and hinting at a vigor fading. I see Borges and Márquez as echoes of Schulz. Yet, as I mentioned, there is a strong Romantic element to Schulz’s writing. One aspect of this is the emphasis on the emotional and the personal over the universal. The pieces barely hint at plot and instead hinge on the expression and changes of mood. Furthermore, there are many odes to nature in these stories, such as an entire chapter to spring dusk in The Street of Crocodiles and a long description of the end of summer in the short story “Autumn.” Yet, in the end Schulz is a recorder of the city. We see dark streets, bustling shops, and haunting city parks.

But my attempts to explain his work do not do justice to Schulz’s inventiveness. For in the midst of his hallucinatory descriptions we also come upon strangely humorous narratives. For instance, “My Father Joins the Fire Brigade” starts with a journey through the darkness by the narrator and his mother:

We entered the wilted boredom of an enormous plain, an area of faded pale breezes that enveloped dully and lazily the yellow distance. A feeling of forlornness rose from the windswept space.

Such drowsiness and lethargy give way to the image of the narrator’s father in a full suit of armor, gleaming like an avenging angel. He is engaged in an argument with the housekeeper about the lack of raspberry syrup in the house. As it turns out, the father is captain of the fire brigade and lets the men under him stay at his house. And they love raspberry syrup. The housekeeper thinks they are a bunch of free loaders, but the father sees them as noble heroes. He tells the housekeeper: “Unable to experience noble flights of fancy, you bear an unconscious grudge against everything that rises above the commonplace.” The story goes on to end with an organized display of acrobatics by the father and his men, but this quotation gets at the Modernist concerns of Schulz’s writing. The city deadens colors and takes the romance away from people’s lives. Yet in this story the father, like Don Quixote, refuses to give in to the status quo of commonness. He wishes to rebel with his adherence to “noble flights of fancy.” This is echoed in the chapter “Tailors’ Dummies” in The Street of Crocodiles:

Only now do I understand the lonely hero who alone had waged war against the fathomless, elemental boredom that strangled the city. Without any support, without recognition on our part, the strangest of men was defending the lost cause of poetry.

And perhaps Schulz’s own art serves a similar function. There is something beautiful and fantastic to be found even in the most gray and base of city scenes. One only has to be sensitive enough to perceive it.

In all honesty, these stories sometimes made me sleepy as I read them. I was lulled by their dreaminess to fall into my own dreams. This says more about my lifestyle than it does about Schulz’s art. Yet it does point to the concentration needed to engage with his stories. This concentration is rewarded with images and worlds that seem of an older time and yet like nothing else you’ve read before. Let Bruno Schulz live on in your imagination.

** My biographical information about Schulz comes from the book, specifically the foreward by Jonathan Safran Foer. Schulz’s writing was translated from Polish by Celina Wieniewska.

There is a long discussion of Bruno Schulz at The New Yorker.

(written August 25, 2012)

The New York Times has an article about the frescoes Schulz painted before his death with some photos:

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/28/arts/design/28wall.html?rref=collection%2Ftimestopic%2FSchulz%2C%20Bruno