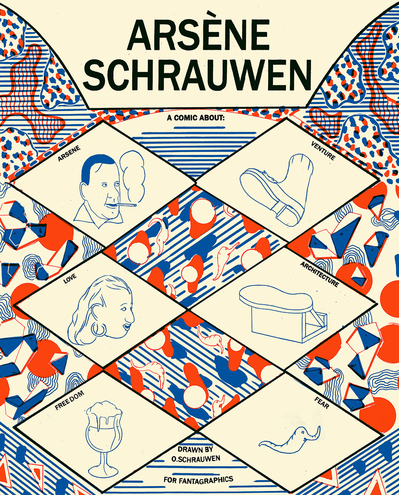

Arsène Schrauwen

Arsène Schrauwen

Olivier Schrauwen

Arsène Schrauwen reminds me a bit of the work of Ben Katchor, with his blocky businessmen engaged in endeavors that seem just outside the real. The book also reminds me of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, in the sense that expectation is often thwarted and any sense of narrative tension is drained by the inanity and passivity of the main character. I make these comparisons to Katchor and Sterne so you understand that this is a book aimed at a particular sensibility, at a reader who enjoys the absurd and the structurally inventive.

So we get a story of the artist’s grandfather, a man-child who moves to a colony- a place that is never named, inhabited by a people we don’t get to see until late in the book- and who spends most of the “adventure” hiding in his bungalow, too afraid to venture out. This is not the story of a hero, nor does it seem to be a critique of colonialism. It’s an anti-story the way that Tristram Shandy is. Yet things do happen. There is an obsession that may be love. A character is committed and receives electro-shock therapy. People get lost. Leopard men come out of the jungle. A city is built. Still, a decisive climax is avoided and all the grandiloquence of the project the colonialists undertake is undercut by the needs of capitalism. At the end, we see Arsène bicycle into the darkness, no more a solid character than he was at the outset.

Besides his playfulness with the absurdity of the story, Oliver Schrauwen is also playful with the layout and drawings of his comic. Colors shift between blues and reds, grids give way to double-page spreads. Schrauwen also uses visual metaphors. When Arsène is arroused he turns into a donkey, like a Belgian Bottom. At other times he becomes a young boy, at others his penis is a bird. Most of the other characters in the comic don’t have faces and instead have simple spheres for heads. At certain moments, their faces emerge, but often quickly disappear again. This may be Schrauwen’s style, but it underscores how little the titular character thinks about other people.

I found the playfulness of this book to be funny and charming. The whole thing was constantly inventive and engaging. At the same time, I can see how this book isn’t for all tastes. Also, I was a bit troubled that a book about a colony in Africa doesn’t have any black people in it. Reality is not Schrauwen’s game here; he is playing more with the European narratives of the great artist and the great adventurer. Still, the lack of a native perspective was at times an unnerving hole in the book.

I read Arsène Schrauwen through my library on the Hoopla app. So if your library has a similar service, you can try it out that way. Or you can get the book from Fantagraphics.