Life? Or Theatre? By Charlotte Salomon – Introduction and pages M004179 and M004211

The rise of the graphic novel is intimately, and of course tragically, tied to the Second World War. If we consider the book that broke through and captured a wider audience and showed the reading public the possibilities of the medium, we look at Maus. But a few proto-graphic novels (to use Jeet Heer’s term for graphic novels published before the term was coined) also come out of experiences relating to WW2. As I’ve written about before, there is Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660, which gave images to the United States’s decision to take constitutional rights away from its citizens. Then there is Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theatre?

In 1938 and at the age of 22, Charlotte Salomon escaped Berlin and took refuge in her grandparents’ home in southern France. But the war kept spreading. Salomon’s grandmother committed suicide. France was taken. And Salomon was murdered in Auschwitz in 1943. Yet in that time, she managed to create an autobiographical work. Yet since she was a painter, she created this work in over 700 gouaches that managed to survive her death and the war.*

As of this writing, there is no edition of this work in print.

That said, many editions have been published over the past few decades. The first edition was published by Viking Press in 1981. The edition I have was published by The Royal Academy of Arts in 1998. The University of Washington Press had an edition in 1999. Apparently an edition was published by Overlook Press in 2017. And Taschen had a hardcover edited version (only 450 of the gouaches) in 2017.

But due to the power of the work and its cultural importance, The Jewish Cultural Quarter has put the entire work online.

What I want to look at is the work itself and I want to analyze it as a graphic novel, looking at its formal structure. I’m only going to take on a few pages at a time. But what I hope you realize is that this work is not merely significant historically, but is also significant as a comic. It is a layered and complicated graphic novel.

Before I start I want to mention how I am going to deal with page numbers. The edition I have has page numbers, of course, and the page numbers were supposed to correspond to the order of the gouaches (1-784), but the book was misprinted and the page numbers are off by 40. The math is simple, but as it turns out Salomon herself numbered the pages, but in her own way. She didn’t seem to include the introductory text pages of her work. So what I want to call page 30, Solomon labeled as page 22. However, it looks as if art historians have given the gouaches a set of numberings. So my page 30 has been given the title “JHM no. 4179” in my edition. The Jewish Cultural Quarter labels this page “M004179.” So I assume 4179 is the standard numbering for the page. Therefore, I’m going to use these numberings, but use the prefix given by The Jewish Cultural Quarter.

M004179

While this work is autobiographical, Salomon has changed the surnames. She has renamed her family Kann, but kept the given names. Her father is still Albert, her mother still Franziska, and she herself still Charlotte. Her grandparents now have the last name Knarre (many of the names have musical references).

The early pages of the work depict the courtship of her parents and the strained relationship between Albert and his parents-in-law. Yet while the family is obviously well-off and upper class, tragedy is a constant theme. Franziska’s sister commits suicide at a young age by drowning. Franziska is determined to become a nurse while the First World War rages. This is how she meets Albert, but since he is a soldier, he has to leave her again soon after their wedding. He manages to return before Charlotte is born. Yet it isn’t long before Franziska falls into depression. She rarely leaves her bed and finds little joy in life. Soon, she begins attempting suicide. At first by poison. While a nurse watches Franziska constantly, Franziska is eventually successful in killing herself.

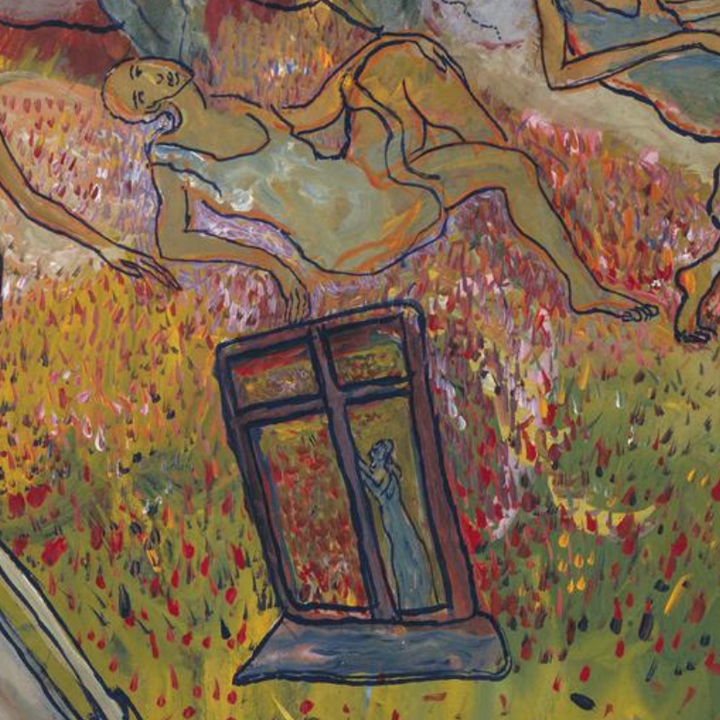

Page M004179 depicts Franziska’s suicide.

The flow of the action on the page follows a “Z” shape. In the top left, we see Franziska in bed, attended by the nurse. The nurse leaves and eventually Franziska rolls out of bed and runs to the window. Yet here the perspective changes. At the bottom of the page we see the bottom of the window sill, as if we were seeing it from Franziska’s perspective. In the darkness at the edge, we can make out a foot.

So the page is framed by the window, which looks in on itself, the window, and in on Franziska’s room. The floor could be carpet, but could also be the grass onto which Franziska falls. It’s sickly green and yellow is shot through with emotional sparks of red.

The languid lines of Franziska and her bed give way to the hard edges of the window frame. The frame itself brings a darkness to the page, echoed by the wood floor of the room in the top right corner.

So we have balance, but also progression and change. But the full import of what the image means only comes with the text. Ironically, Franziska’s thoughts of “I’m always so alone” are contrasted with the multiple figures in the image. Yet we understand the mentality that leads her to the beckoning darkness of the window and beyond.

That darkness of the window frame hangs at the bottom of the image. Even as we view the rest of the page, its large form looms in our peripheral vision. We cannot escape thinking of it just as Franziska cannot.

As Judith Belinfante points out, Salomon wrote the text for the first set of gouaches on tracing paper that was placed over each gouache (34). So the text layer is an overlay, the position of the words corresponding to who is speaking or what is happening in the scene. I wish an edition existed where we could see these overlays placed over the gouaches. As you can see, Franziska’s thoughts are inscribed over her body. So Salomon makes her thoughts and body inhabit the same space.

Yet notice that neither the actual act nor its effect are depicted here. Salomon does show Franziska’s body two pages later, but keeps page M004179 focused on her mother’s decision and the scene of the act. As readers, this puts us in Franziska’s mental space. We are not seeing her as an object, but as a person compelled by dark emotions. The riot of colors add to these emotions. This is made all the more poignant when we realize that what we are seeing on this page is decision made by an artist about how to depict her own mother’s suicide.

M004211

Eventually, Charlotte’s father, Albert, remarries. Scene 3 of the book depicts the life of Paulinka Bimbam and how she ended up becoming Charlotte’s step-mother.

Page M004211 depicts the years of Paulinka’s life after her father dies. The page is organized as a series of strips that are read left to right, like a layer of newspaper comics. In strip one we see Paulinka as a teacher and the obsessive nature of some of her students. The second tier shows Paulinka at her father’s grave. Tier three gives her move to the big city. Tier four shows us the menial jobs that she performed. Yet tier five shows us that at heart Paulinka is still an intellectual and a student. And so tier six gives us the defining moment when Paulinka returns to school and ends up assisting a forgetful professor.

Each tier is set off by its own dominant color: red, green, yellow, et cetera. This makes it clear to us that each strip is its own discrete scene. As with the other pages, Salomon uses repetition of figure to show either the physical or mental progression of her character.

The text describes all these various progressions and tells us what they are. But having all of them on one page shows the weight of all these events and the sudden changes in environment and fortune that Paulinka goes through in her early life.

Also, Salomon shows Paulinka looking back in the end. This position makes no sense in terms of the action. This is the scene where she is assisting the professor with her own knowledge. So we would expect her eyes to be on him or on the class. Yet by making her glance backward, Salomon makes Paulinka consider where she has come from and all that she has endured to get to this point in her life. We see her reflective thought. So we get not only the action, but the thoughts of the character. This subtle choice of body position adds a greater depth to the page than if Salomon had just focused on depicting the realistic actions of Paulinka.

Looking at both of these pages, we see an artist who is finding ways to depict the internal world in a visual medium. She is finding creative solutions. Yes, Salomon uses text, but she also uses color, framing, and body position to convey emotions and thoughts.

* If you want to know more of the story, I recommend this overview by Neglected Books and this article at The New York Times.

Works cited

Belinfante, Judith C.E.. “Theatre? Remarks on a Work of Art.” Charlotte Salomon Life? Or Theatre?. Royal Academy of Arts, 1998. 31-39.

Salomon, Charlotte. Life? Or Theatre?. Royal Academy of Arts, 1998. Translated by Leila Vennewitz.