Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms by Fumiyo Kouno

I first read this book as a scanlation, but Last Gasp has published an official translation.

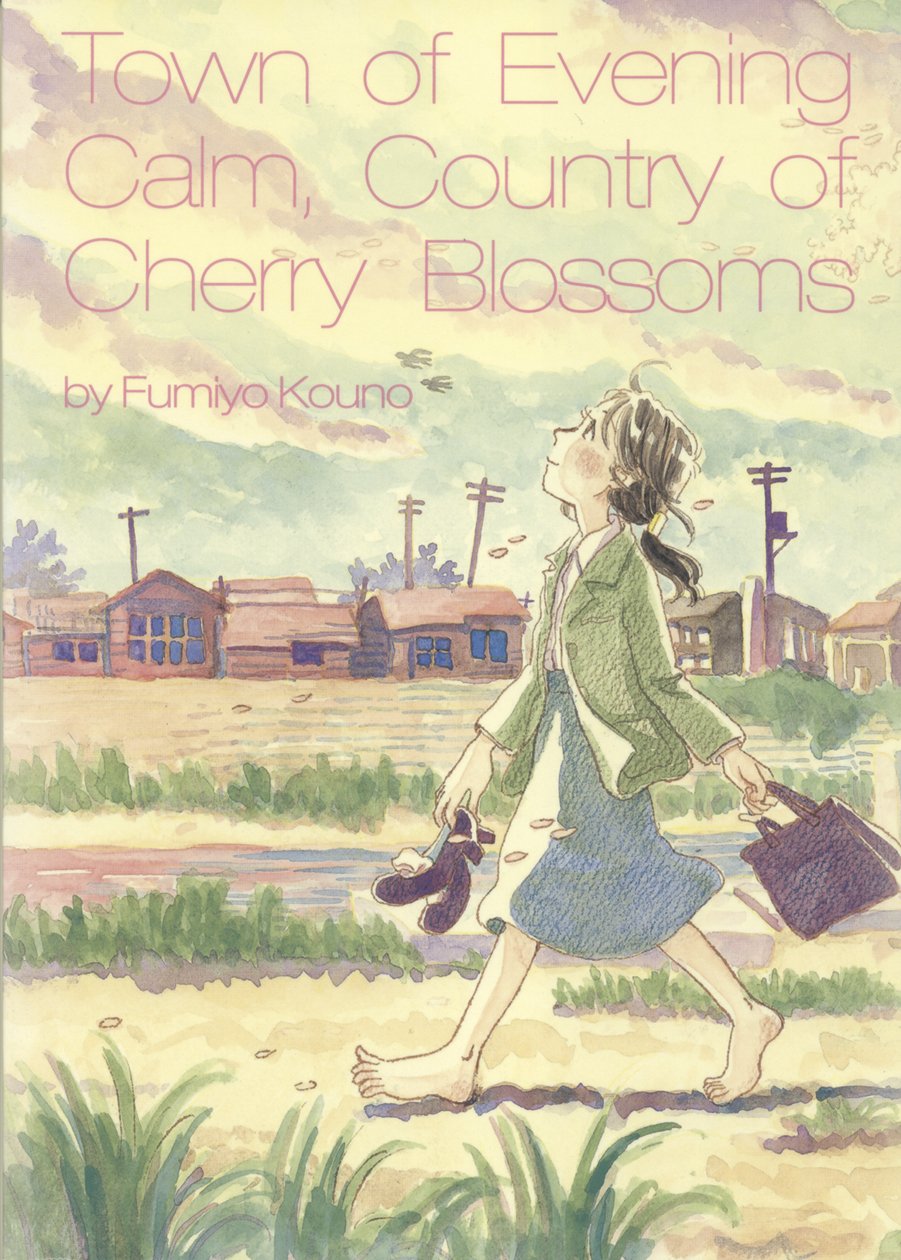

If you know nothing about this book, a quick glance at the cover might be misleading. The soft pastels and open lines may give you the idea that this is a book about the tender and quiet sides of life. This isn’t entirely incorrect, but the focus of this graphic novel is the long-term effects of war, specifically the effects on people years after the dropping of the hydrogen bomb on Hiroshima on August 6 of 1945. Yet, this is not a dark and fatalistic book either. The tension between the open, almost sweet art and the serious, horrific subject matter is one of the strengths of this book. The one serves to temper the other and keeps the story from veering too far into melodrama. Kouno further manages to avoid an overbearing reading experience by focusing on the small details of everyday life. Obviously, many details are ones Kouno has observed, but many are also due to her research. In the notes at the end, Kouno shows us the scope of this research. But unlike a lot of literary fiction, the research doesn’t overpower the story. Kouno’s focus is on the human experience inside all of the facts and dates. For instance, the fact that the character on the cover is shoeless is due to something Kouno read in an autobiography. It’s a very specific detail concerning how the survivors of Hiroshima rationed everything they owned, since there was little industry and little money to get bare necessities such as shoes. This being a graphic novel, Kouno doesn’t have to talk about the act; she can just show it. Details like this create a level of realism and authority to this work.

As the comma in the title suggests, there are two stories in this book, but they are interrelated. The first story, “Town of Evening Calm,” is set ten years after the blast. The main character lives in a shanty town next to the river and signs in the background let us know that the residents are in danger of being evicted (we actually see the same location in the second story, but I’ll get to this later). The main character, Minami, is a young woman trying to live a normal life, but unable to do so. The main reason for this is the survivor’s guilt that she feels. It not only stems from having lived while so many, including family members, died, but also comes from the belief that she could have helped more people than she did. Minami doesn’t obsess about this; we only see these thoughts at certain moments. One time is when she is at a bath and all the women there bear the scars and blemishes of having survived the blast. An artist using a more realistic style would focus on the physicality of these wounds. Yet since Kouno employs such a simple style, we understand the sisterhood that these marks create while not being disgusted by them. Her style choice also serves her well later when she depicts a bridge strewn with corpses. In Kouno’s hands, the corpses are not much more than stick figures and the scene becomes about Minami’s mindset, not about the horror of the bomb blast. That horror is a given; Kouno’s focus is on the personal and social repercussions of that horror. This story also has the most formalistic play of the two in the book. Kouno uses full-bleed panels, panels turned on their sides, and empty panels to incredible effect. A lot of manga employ similar tricks, but only to enliven the page design. And these, like similar effects employed by their American counterparts in superhero comic books, only serve to kill the visual narrative. Kouno, on the other hand, uses these tricks sparingly to reinforce the story itself. In her hands, such simple little formal changes have a lot of impact. I’d give you examples, but I don’t want to give away more of the story than I already have.

The second story, “Country of Cherry Blossoms,” takes place even longer after the bomb. A new generation is growing up and Hiroshima is more like a regular city. Yet the effects of the bomb still linger. Sometimes these effects manifest themselves in poor health or death, but Kouno again is more interested in the social and emotional effects. What this story deals with, through the eyes of a girl (who becomes a young woman in part two), is how people have come to see the survivors of the blast. It is not talked about much in the open, but survivors of the bomb and their children are a kind of untouchable class. You never know when they may die or if your offspring with them may be tainted, so it’s best to avoid them. It is Kouno’s honesty about this social shunning that caused the book to be controversial in Japan. And this is a side to the experience that I’ve never read about before.

As I mentioned above, the two stories are interrelated. Part of the joy in the reading experience is discovering these connections, so I don’t want to give too much away. One thing I will say though, is that you should pay attention to names. But the biggest effect of having these two stories appear together is that you understand the long-term effects of war as well as the fact that people always move on. The shantytown of the first story is now a riverside park in the second. Yet even though the bomb happened a decade or more ago, people still continue to die, sometimes suddenly. And pain and sorrow are etched into the social interactions. Yet in spite of all this, people sing popular songs, argue with their family members, and fall in love. The endurance of the human spirit, no matter how petty or how lovely, is what comes through here. Putting this into words oversimplifies it and perhaps makes it seem trite. But as you read the story, this theme is anything but trite. This is partly because characters simply up and die. Personal tragedy is placed side-by-side with generational progress. This is a book that chills you at the same time as it warms you.

Since I first read Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms on-line, I’d like to compare the two translations. In the Kotonoha scanlation, the sentences are longer and more nuanced. I assume (I don’t read Japanese) this is a more literal translation. The sentences in the Last Gasp translation are shorter, but they read more easily. The cadence is less stilted and lines flow better from one to the next. So I think the Kotonoha scanlation is more exact, but I prefer reading Last Gasp’s version. Another nice decision is that they put all the notes on the text at the end. Most of the notes are Kouno’s, but editorial ones are sprinkled in for U.S. readers. This means that there are no distracting asterisks or footnotes in the story itself. This is a common practice in scanlation, and when stories are released at about ten pages at a time it makes sense. These notes help, but they do distract from the story itself. I prefer having them at the end for me to refer to if and when I want to.

After I had read the scanlation of this book, I decided to support the artist and buy a copy of the original, even though I couldn’t read Japanese. This wasn’t entirely a selfless act; I also wanted to be able to closely examine the art. What I want to mention though is how identical the original and the Last Gasp editions are. The Japanese edition has yellow endpapers and the cover is a removable dust jacket, but beyond that there are not many other differences between the two versions. What this says to me is that Last Gasp was committed to providing an edition that reflected as closely as possible the artist’s original intent. I applaud them for this.

This is a quiet little book that I can see easily slipping beneath most people’s radar. And that’d be a pity, because Kouno has given us such a wonderful reading experience. She is a master craftsperson with a keen eye on the strength and fragility of the human heart. Her kind of artistic honesty will always be needed, but seems especially poignant for people in the U.S. these days.

The above was first posted May 14, 2007. It received the following comment:

Information from Japan

I have read your blog very interesting.

I will be glad if you enjoy some information about the comic.

In the original edition, there is an illustration of paper cutout below the cover.

It was a book jacket of publication on her own account.

What was the difference of clothes between Minami and colleagues?

The story of the Town of Evening Calm started on July.

(You can find date on the postcard stamp from Asahi)

It is very hot season, but Minami always wear long sleeve shirts.

She intended to hide the scars on her arm.

Can you find when she stopped hiding the scar for Yutaka?

Why Nanami Played baseball eagerly?

Her father loved it, however his son couldn’t play it.

Because Nanami felt loneliness about relationship between the father and she, she wanted to gain a praise from him.

Ete,

Thanks so much. I hadn’t noticed the bit about the long sleeve shirt. On page 2 of the story (page 6 of the book), Minami looks at a dress and says she won’t wear it. I had assumed it was because she doesn’t want to pamper herself with nice clothes; she feels like she doesn’t deserve them. But the first panel accentuates the fact that the dress is sleeveless. Then, as you point out, we see on page 15 that she has scars on her forearms. So yes, she’s been covering them up all this time. And we don’t see her scars again until the final panel on page 34. I hadn’t noticed that.

I had noticed the baseball connection. Though I don’t think that Nanami plays baseball only to be closer to her father. Yet I’m curious if there’s any significance to the fact that when Nanami gets hit with a ball (page 42) the coach asks if any fourth graders want to replace her, but Nanami’s a fifth grader. Is it because she’s a girl? Because she’s a bad player? Or do the younger kids only get to play when an older kid is injured or absent?

Also, on page 51 we learn that Toko had stayed up all night rewriting her essay about her dreams for the future. Is that because she knew then that she wanted to be with Nagio? Or because she had decided to be a nurse? Or both, maybe.

Thanks again for your comments. It makes me want to reread the book more closely. It’s such a rich piece of work. I hope more people read it.

the following was originally posted January 28, 2010

Town of Evening Calm, Country of Habitual Denial

Over at The Hooded Utilitarian, Ng Suat Tong has a review of Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms. He has a very particular take on the book, situating it into a larger context of books about Hiroshima in Japan. His main thesis is that Kouno’s graphic novel fits a self-pitying pattern in Japanese depictions of Hiroshima, a pattern that completely ignores Japanese culpability. I haven’t read all the same books Tong has, so I have trouble getting as hot under the collar as he does. Still, I have seen how the Japanese, at least the Japanese government, has time and again denied its own role in some of the atrocities of that war. For instance, Japan has denied or distorted its alleged role in the Rape of Nanking. Likewise, Japan has also denied its alleged treatment of Koreans, especially Korean “comfort women.” On a personal note, I once had an older student who had grown up in Japan who exhibited the same mentality. In the class he was in, we read Native Speaker which briefly mentions the Japanese mistreatment of Koreans during World War Two. This student, though he had left Japan years ago and in fact was unhappy with the Japanese government, wrote an entire essay about how I was a brainwashed American promoting lies about the Japanese because I had students read this novel. So it’s interesting to me to see this denial as a larger cultural mindset and seeing Kouno as being part of it.

Still, I like her book. Jog’s response (number 15) to Tong’s review matches my own sentiments and he words his thoughts much more respectfully than I could.