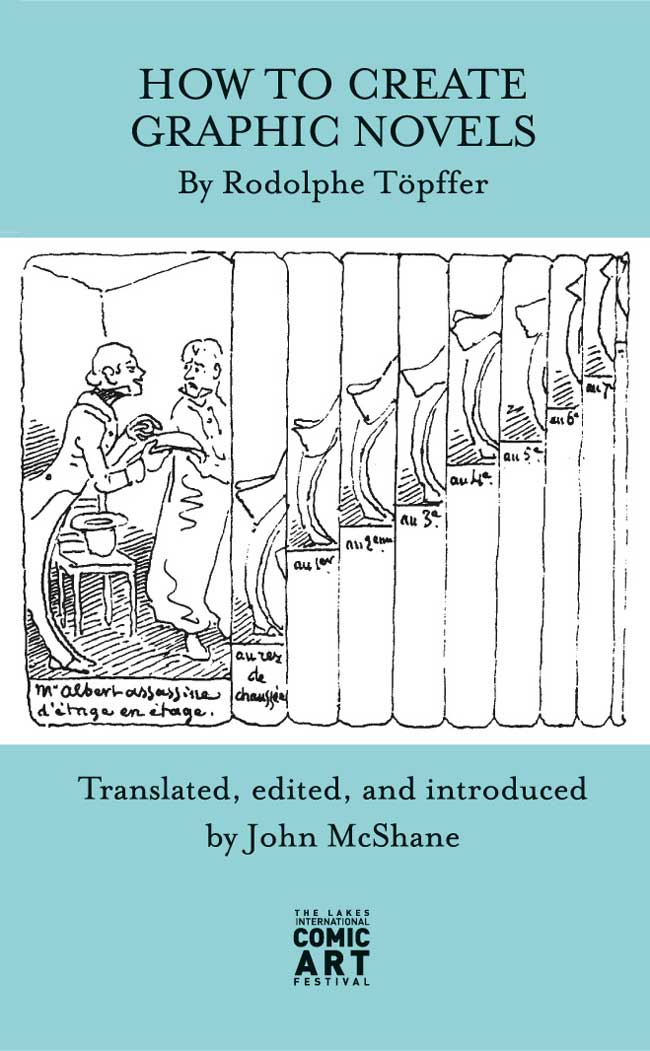

How to Create Graphic Novels by Rodolphe Töpffer

Rodolphe Töpffer usually wins credit for being the first comics artist. He put multiple panels on a page and employed the new advancements in printing to get his work read. He may not have used word balloons, but most of the elements of contemporary comics started with him. What I didn’t know (and maybe you didn’t either) is that he also was one of the first theorists about this new medium. In 1845 Töpffer wrote Essai de Physiognomie, his thoughts on what made littérature en estampes (as he called it) so special. Sorry, Will Eisner.

I learned this because a new translation was recently published under the title How to Create Graphic Novels, translated and edited by John McShane. While I understand the need for a better title than “Essay on Physiognomy,” “How to Create Graphic Novels” is a bit misleading. Still, this is a very interesting little book and I’m really glad this new edition exists.

I just want to mention that the introduction to this book is both helpful and confusing. It gives a bit of background on Töpffer and goes over what parts of Essai de Physiognomie of have been cut for this edition. But the unrestrained enthusiasm and unfocused chronological jumps make it hard to tell when the opinions being described are Töpffer’s, his time period’s, or the editor’s. Also, almost half the introduction talks about contemporary works. I understand that McShane is trying to contextualize Töpffer’s influence, but it makes for a muddle of times and ideas that obfuscate more than illuminate. That being said, McShane’s translation of the main text is very readable and engaging.

As Töpffer’s original title implies, most of his book concerns facial expressions and how what characters look like reveals their personalities. Töpffer does mention some other ideas in the beginning. The one I found most interesting is that an artist can use multiple panels in quick succession as a kind of visual hyperbole. Yet he doesn’t say much more than that; most of the book discusses physiognomy.

I was concerned when I first saw this term used. Physiognomy usually goes hand-in-hand with prejudice. The very idea of it, that we can judge people’s personalities based on their looks, is the definition of pre-judging. And yet so much of what we do as artists in comics is based in this. We convey character through visual signifiers. This is something that has always troubled me since there are so many examples of how this can go horribly, even fatally, wrong. All you have to do is look at the hooked noses and dark skin in the history of Disney villains to find one example. While he never mentions racial profiling or caricature used as warmongering, Töpffer understands that physiognomy has its limits. He emphasizes that the types of visual signifiers he discusses are about drawings and don’t always relate to “nature.” He says, “these signs never present, neither when considered in isolation, nor when considered together, an infallible criterion by which to judge the intellectual or moral faculties.”

What is so refreshing about his approach is his sense of play. Töpffer says that an artist doesn’t have to go to school and study anatomy. All they need to do is sketch faces, no matter how simple, and play around with the features. See what happens when you move the eyebrows, the lips, or the nostrils. Observe what kinds of characters reveal themselves from these shifts. He then encourages artists to mix up these signifiers. He shows the result of drawing a mouth that denotes laughter with eyes that imply crying. It is this subtle interplay between these different features that Töpffer feels is the medium’s strength and what advantage it has over the novel. And so we see, even in the earliest essay on comics, this bid to prove that it is as worthy a medium as writing.

This is a short book, but a fascinating one. I can see how some of Töpffer’s ideas could be easily made into exercises for a class on creating comics. And again, I was really charmed by Töpffer’s tone. He is an enthusiastic proponent of this new medium, but he is also a practicing artist who is thoughtful about the realities of what he is doing. This book helped me not only respect Töpffer but like him.

A translation was already published in early 2017: https://www.amazon.com/Inventing-Comics-Translation-Reflections-Storytelling/dp/1602358699

I know this is years later, but I just wanted to say that I later got Figueiredo’s translation of Töpffer, Inventing Comics. It’s a fuller book and a nice translation. It also reprints the text in French as well as English. I recommend it highly.