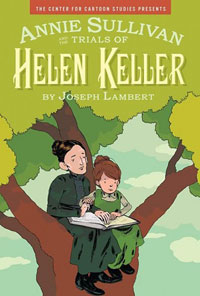

Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller by Joseph Lambert

The story of Helen Keller is a famous one and one that has been told many times. So if an artist were tasked with telling the tale, there are many possible versions of the story to look to for inspiration or perhaps fall into the trap of imitating. Yet what Joseph Lambert has created is not simply a Classics Illustrated retelling Keller’s autobiography or a static version of The Miracle Worker, but a book that lives and breathes as a graphic novel, using the medium to its full advantage. Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller is a book that should be on everyone’s permanent “best-of” lists.

Lambert had the challenge of making an old story new again yet readable to an all-ages audience. Upon flipping through the book, the first thing one notices is how Lambert has chosen to depict Helen’s world. Forms only appear in rough outline, with color denoting the separation of self and other. Over the course of the book, sign language starts appearing in the darkness, gradually to be replaced by words. The visual device both accents Helen’s isolation– she is literally in blackness– and makes it clear how she comes to understand language. The images and words in Helen’s world get more complicated as her understanding grows.

Lambert uses the static medium shot in vogue among people like Jason and Chris Ware. Of course, it is also also a style used by the early newspaper strips, such as King’s Gasoline Alley. Here the technique serves to let the drama unfold naturally without any potentially bathetic use of close-ups or fancy framing. Still, at times I felt too separate from the action. For instance, I didn’t understand at first that Annie was spelling words out on Helen’s hand. Since the hands were so small I didn’t realize the significance at first. Yet in general, the restrained compositions of the book make the actions of the characters come to life by heightening the small changes in their faces and posture.

Yet this book has more going for it than its formal decisions. One thing I’ve always felt that comics tend to lack is depth of characterization. For all the talk about “literary” comics, I think the majority of comics don’t get to the complexity of characterization that literature does. Yet Lambert’s book is not guilty of this fault. Overall, this book is a close character study of Annie Sullivan. We come to understand why she is uniquely able to get through to Helen, seeing both depictions of her experiences and expressions of her temperament. And Lambert doesn’t put Annie on a pedestal or candy-coat things. Annie is hot-headed and quick to vindictiveness. And by the end, I began to feel that she was too possessive of Helen. Not only does she keep people away from Helen, but it becomes clear that Helen’s sense of reality is mediated by Annie. Helen’s knowledge that the warmth that she feels is actually the sunlight through the trees or the fact that a story is fact or fantasy is dependent solely on Annie Sullivan. And in the end, we see the possibility that this is too claustrophobic a reality. Yet again, what Annie does is just an amplified version of what all parents do. On top of that, who else and how else could Helen be reached? And so, I was left thinking that it couldn’t have been any other way.

Such musings point to the complexity of Lambert’s book. Lambert doesn’t shy away from these complexities and he notices (or creates) many subtle details. And, thankfully, he doesn’t judge. For instance, on page 52 we see Mrs. Keller’s day and how being a housewife in that era was a full-time job. After nine panels depicting her work, her husband and brother return home (from doing what?) and her brother asks with unthinking privilege, “Dinner ready?” We understand Lambert’s point if we choose to, but he doesn’t belabor it. Nothing more is said and Mrs. Keller goes off to make dinner as a woman of her time would. This scene is not simply a feminist political statement; it helps to underscore Annie Sullivan’s reality. If she cannot have the job teaching Helen then what autonomy she has will be gone. Again, no character says this, but we understand it due to Lambert’s staging.

Such incredible restraint and trust of the reader are the hallmarks of a cartoonist in complete control of his craft. That and the deep understanding– and at times frustration– we come to feel for Annie make this a truly remarkable book.

The main quibble I have is with the ending. I think it may have required a firmer authorial hand. Lambert depicts the events of the plagiarism trial against Helen and allows a certain amount of vagueness about what actually happened, at least in terms of how much Annie Sullivan may have coached Helen to cover up the truth. This works and it creates a sense of doubt in the reader about Annie’s methods and we can see it creates doubt for Helen about her own sense of reality and herself. Yet the important thing is the relationship between Helen and Annie. With the trial we see a whole new side of that relationship; a strain is put upon the trust that the relationship is founded on. In other words, what is Helen thinking? How does she feel about Annie now? And this is left unanswered. The book ends here. It’s as if a door is opened in a house and a new room is revealed, but we are quickly told that we cannot enter and must in fact go home. And so I feel that the main relationship in the book, the one between Annie and Helen, is left in limbo. And so the book ends more with uncertainty than resolution. On the other hand, maybe I’m accusing Lambert for lacking the very thing I lauded him for earlier: lack of drama.

Besides this minor reservation about the choice of ending, I find Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller to be an incredibly strong book. In fact, it’s a book I’m going to add to the short list of graphic novels I will suggest to people who don’t read comics. It is such a solid work with such unassailable strengths that it will appeal to almost any reader. This is a book more people should be talking about. I hope it gets the attention it deserves.

Other reviews:

Rob Clough The Comics Journal website

(written August 27, 2012)